Volatile financial markets, events in your life, and even regular investment reviews can prompt you to wonder why we rebalance your portfolio. After all, if your strongest-performing assets account for a larger portion of your holdings, why not let them ride?

It all comes down to risk.

Appropriately balancing risk and returns. When we initially drew up your investing plan together, we weighed several factors: Your income, age, and your financial goals, among other things. We built your portfolio based on your unique goals and incorporated some market-return assumptions. The resulting portfolio’s allocation balances the potential returns you’ll need to reach your goals with the risk of potential losses you may incur.

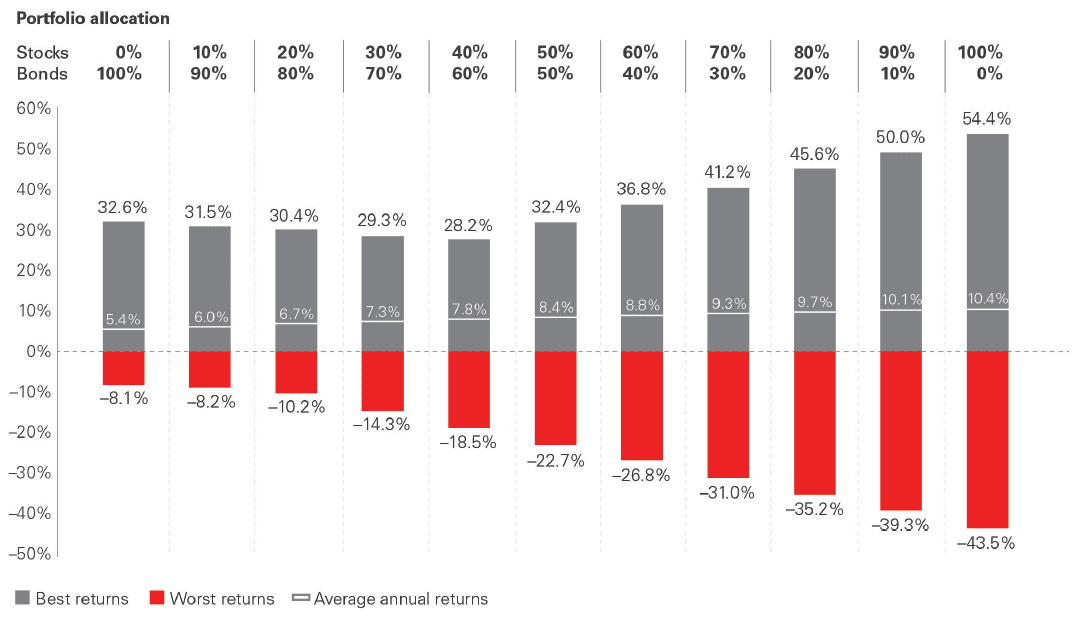

In other words, the purpose of rebalancing isn’t to score the maximum returns possible. The purpose is to manage risk, so your nest egg might fluctuate less in the event of a downturn. The chart below visualizes the concept. Historically, as the percentage of equities in a portfolio has increased, so have the portfolio’s returns. But there’s a trade-off: the higher the percentage of stocks, the greater the risk of losing money.

Historically, higher-return assets have brought increased risk

Best, worst, and average returns for various stock/bond allocations, 1926-2020

Source: Vanguard.

Notes: Stocks are represented by the Standard & Poor’s 90 Index from 1926 through March 3, 1957; the S&P 500 Index from March 4, 1957; the Dow Jones Wilshire 5000 Index from 1975 through April, 2005; the MSCI US Broad Market Index from April 23, 2005, to June 2, 2013; and the CRSP US Total Market Index thereafter. Bonds are represented by the S&P High Grade Corporate Index from 1926 through 1968; the Citigroup High Grade Index from 1969 through 1972; the Lehman Brothers U.S. Long Credit AA Index from 1973 through 1975; the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index from 1976 to 2009; and the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Float Adjusted Bond Index thereafter. Data are through December 31, 2020.

Past performance does not guarantee of future returns. The performance of an index is not an exact representation of any particular investment, as you cannot invest directly in an index.

One way to think of it: Imagine you’re a baseball manager looking to put together a team. You have a limited number of slots and a finite budget. You could go with a big-name slugger who hits lots of home runs—and commands a hefty contract. Alternatively, you could use that same budget amount to pick up a few less flashy players—who happen to be really consistent at hitting singles and doubles.

Your analysis shows that having a player with a higher on-base percentage in the lineup equates to more wins than having a player with a lot of homers. You could also reduce your risk by spreading out the investment over a few “quality” players rather than just one. So it makes sense for you to sign players who have the potential to get more base hits.

Similar reasoning is at work when you maintain a diverse, balanced portfolio with a disciplined commitment to an established asset allocation—for example, a portfolio made up of 60% stocks and 40% bonds. If you require relatively consistent returns (for instance, if you’re generating income from your portfolio and want that income to remain steady), bonds serve to dampen the market volatility that might otherwise disrupt steady returns.